Community settings are an effective, accessible option for many seeking care

The treatment gap continues to be an obstacle in addressing opioid use disorder (OUD) in the U.S. In 2018, an estimated 2 million Americans had OUD but only about 26% received any addiction treatment.

Some patients and policymakers assume that the best course of treatment for OUD is in an inpatient setting, despite evidence to the contrary and guidance from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). As of 2017, 60% of U.S. residential facilities did not offer any Food and Drug Administration-approved medication to treat OUD, the gold standard treatment for this disorder.

As shown in Pew’s recent video, outpatient treatment in the community provides several benefits and an appropriate level of care for many individuals, especially people with a less severe OUD according to diagnostic criteria. As demonstrated by David Zee, an outpatient recovery advocate, outpatient treatment allows people to live in their communities, retain employment and/or education, and remain near their support networks, including family and friends. Moreover, outpatient treatment generally costs less than inpatient treatment.

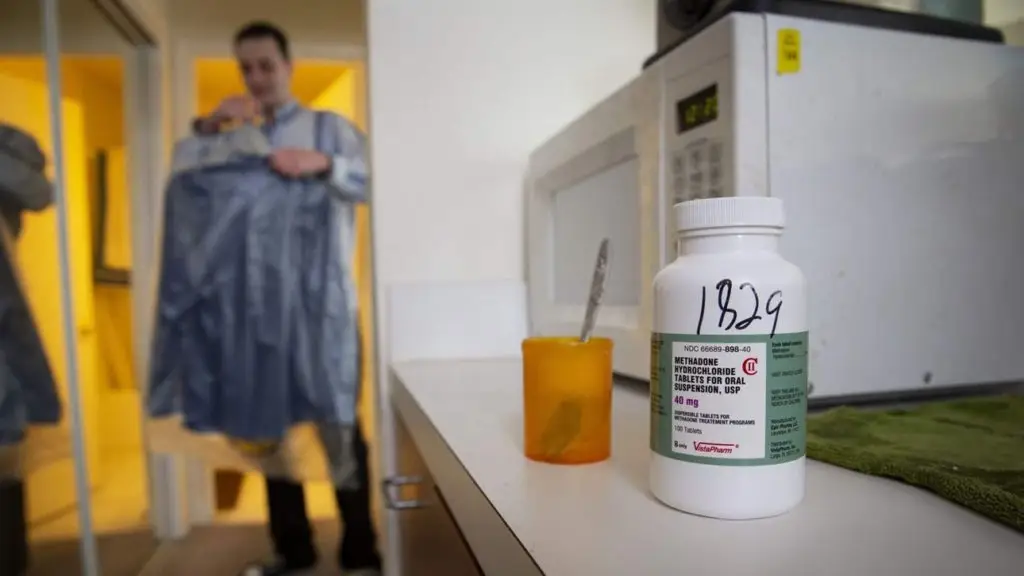

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, the federal government has eased restrictions for OUD treatment by allowing take-home methadone doses of two weeks or longer; initial buprenorphine consultations taking place via telephone or videoconference; and the use of telehealth for counseling, making outpatient care more accessible than ever before. These allowances can also help patients begin or remain in treatment while practicing physical distancing, one of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s chief recommendations for slowing the spread of coronavirus.

Outpatient treatment options

Outpatient treatment in the community can be accessed at opioid treatment programs (OTPs), in office-based primary care settings, and in other settings that provide intensive outpatient treatment. OTPs are treatment facilities that provide OUD medications, counseling, and other health care services. They are the only outpatient treatment setting in which individuals can access methadone, one of three FDA-approved medications that doctors use to treat OUD. Some programs also offer buprenorphine and naltrexone, the other two approved medications.

Office-based opioid treatment allows primary care providers to prescribe OUD medications in their own clinical settings. Although these providers are not legally required to offer behavioral health services, such services are sometimes available on-site, or patients may receive a referral for counseling. Providers with the appropriate authority may prescribe buprenorphine as a take-home prescription; naltrexone is administered once a month in the clinical setting.

For individuals who require more services, intensive outpatient treatment programs represent a higher level of care than traditional outpatient settings. These programs can offer individual and group counseling, skills development and support, and medication.

The medications to treat OUD—methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine—have been proven to have the best outcomes, in part because they:

- Block effects of illicit opioids.

- Reduce or eliminate opioid cravings.

- Reduce or eliminate withdrawal symptoms (methadone and buprenorphine only).

Barriers to accessing outpatient treatment

A number of individual and systemic hurdles keep people who need treatment from accessing it, ranging from out-of-pocket expenses to restrictive state policies and regulations. Stigma also serves as a barrier by perpetuating the falsehood that OUD is a moral failure and that individuals who receive medication are substituting one drug for another. This misconception discourages individuals from seeking help, even though evidence shows that medication allows people to live productive lives. Stigma may also lead to less availability of OTPs and health care providers who can treat OUD. When community residents and policymakers do not understand the value of these programs, they may not support the opening and expansion of OTPs.

Strict federal and state regulations imposed on OTPs further limit access to methadone treatment. And although buprenorphine can be prescribed in primary care settings, it is also subject to stringent requirements. For example, providers can prescribe the medication only after completing additional SAMHSA training and obtaining a Drug Enforcement Administration waiver, and are subject to additional federal scrutiny. As a consequence, there remains a shortage of providers prescribing buprenorphine. In 2017, 44% of counties did not have a single physician authorized to prescribe the medication.

Expanding outpatient treatment

Greater access to outpatient OUD treatment must be a priority for policymakers. Approaches may include amending laws and regulations that impose moratoriums or statutory caps on the number of OTPs permitted in states; allocating public funding to support more providers becoming waivered to prescribe buprenorphine and Medicaid coverage of medications for OUD; easing strict requirements for prescribing buprenorphine; and supporting efforts to reduce stigma. These policy changes could make outpatient treatment and medications more readily available and ultimately encourage more people with the disorder to seek effective care.

Beth Connolly is a director, Sheri Doyle is an associate manager, and Vanessa Baaklini is an associate with Pew’s substance use prevention and treatment initiative.

Article Title: "More Outpatient Treatment Needed for Opioid Use Disorder"

Originally published by The Pew Charitable Trusts on April 30, 2020.

Authors: Beth Connolly, Sheri Doyle, & Vanessa Baaklini.

Read the original article here.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of REACH Health Services. This content is reprinted for informational purposes and is in compliance with Pew's reprint permissions.

Hi to every single one, it’s really a good for me to pay a quick visit this web site, it consists of helpful Information.